An observer may ask whether a difference is significant. This seemingly simple question requires a nuanced answer, because there is an important distinction between statistical significance and practical significance.

Statistical significance

The sample mean or proportion is typically the best estimate of the population mean or proportion. We can use p values or, better yet, confidence intervals to determine whether efficacy or safety differences between two products, or between a product and a placebo, are statistically significant. While this may at first sound pretty straightforward, a few thorny issues quickly arise.

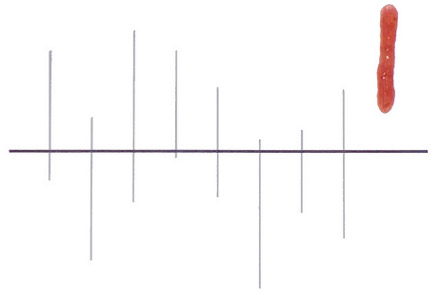

Beyond the absolute difference in means and proportions, three factors influence whether outcome comparisons between a clinical trial’s arms are statistically significant: A) the sample size, B) the amount of variability, and C) the confidence level. Pharma and biotech manufacturers can impact the first two, and the industry standard for the third is 95%.

Study designs with larger samples can be more representative and allow for subgroup analyses. However, study designs with very large samples boost the likelihood of achieving statistically significant differences. The hazard here is that a very small difference can be statistically significant if the sample size is large enough. Even more perilous, very large samples can yield statistically significant differences that are not real.

Study designs with stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria will, by definition, decrease the variability in the sample and could decrease the variability of the outcomes of interest. This decreased dispersion can better the chances of finding a statistically significant difference. However, the ability to generalize results to real-world populations diminishes as the inclusion and exclusion criteria homogenize the sample. This reflects the classic tradeoff between internal and external validity.

Not to get too technical, but the p values and confidence intervals commonly used for significance testing are based on sampling logic assumptions. As such, they apply only to results based on a sample. These tests are not appropriate if the analysis is based on data for the entire population (N) versus a sample (n) drawn from that population. This is an increasingly common scenario, such as when integrated delivery networks like Kaiser Permanente mine their electronic medical records for all their covered lives.

Practical significance

Tests to measure statistical significance and judgments that evaluate practical significance are unrelated. A difference that is a statistically significant outcome may not be practically (clinically or economically) significant, and vice versa. For example, the practical significance of a treatment that decreases average length of stay (LOS) by 0.2 days, which translates to 4.8 hours, is not likely to be meaningful to a payer, given that most hospital contracts are based on DRG or per diem, not hourly, rates — but may be meaningful to the hospital in terms of cost reduction.

Practical significance — clinical or economic — is subjective, but is critical for making sound business decisions. Expert judgment or opinion is often used as the basis for determining whether a difference in absolute or relative terms is practically significant. The expert judgment depends on the context and can be derived from key opinion leaders, clinicians, patients, or caregivers.

No matter the perspective, and regardless of whether the result is statistically significant, assessing the practical significance of a difference must answer the “So what?” question. Whereas statistical significance is based on a selected confidence level, there is no clear-cut guidance for practical significance. Translating differences into estimated cost impacts can help decision makers evaluate the practical significance of a difference, although doing so for surrogate endpoints/markers or intermediate health outcomes is fraught with difficulties and almost never clear-cut.

Payers’ views of significance

Payers are very sophisticated and make a distinction between statistically and practically significant differences. A statistically significant difference is necessary but not sufficient to payers. To have an impact on formulary and medical policy decisions, the difference must also be viewed as clinically or economically significant.

Payers are frustrated with ambiguous communications from manufacturers that state a difference is “significant.” Too often, the manufacturer is simply reporting that the difference is significant without specifying that it is “statistically significant.” Pharmacy and medical directors reviewing a manufacturer’s marketing materials are quick to say that they’ll have to review the results — a process during which they’ll confirm that the “significant” difference is statistical and critically evaluate the practical significance of the differences.

If a manufacturer believes a difference emerging from a trial is practically significant, then, to the extent they can do so without risking off-label promotion, they should make that case as clearly and convincingly as possible. Some manufacturers may even have convincing evidence that a difference can positively impact payers’ budgets. At the end of the day, payers will decide whether or not they believe a difference is significant.

No Comments