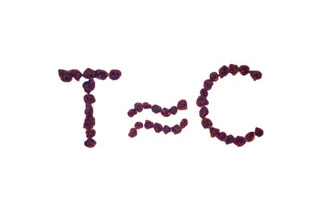

Yes, sometimes payers view “non-inferior” products as being superior. Just how they react to new products with evidence of non-inferiority depends, of course, on the context. Before jumping into different market scenarios, let’s first explore the concept of non-inferiority.

Say what?

Our language often plays with the notion of non-inferiority. In reference to, say, a meal, you’ve probably heard someone say (or said yourself), “not bad.” Depending on the context, the food could have been fair (but not bad), good, or even great; without context, the valuation is ambiguous and left open to interpretation. Our language is replete with these double negatives that grammarians refer to as litotes. Getting one’s arms around the concept is not difficult — but does that mean it is easy?

Relativity

Payers evaluate late entrants relative to the alternatives for two key reasons: (1) payers crave comparative effectiveness research (CER), and (2) payers have to use CER when it’s all that is available, such as when clinical trials with active comparators intentionally lack placebos for ethical reasons. Trials can be designed to yield evidence of relative superiority or, curiously, non-inferiority. Technically speaking, non-inferiority can’t be proven, although one can find statistical evidence of superiority or inferiority. The intended meaning of the term non-inferiority is that any difference is small and not statistically significant. And while no manufacturer seeks to demonstrate inferiority, that too is a potential outcome.

Things get murky right out of the gates when selecting the comparator, and payers are often critical of the choice. Payers may prefer a comparator widely viewed as the standard of care or a comparator with a commanding market share. In contrast, manufacturers may frustrate payers and choose to compare performance against a product within the same class or having the same mechanism of action in a supposed attempt to make apple-to-apple comparisons. But a “cleaner” comparison may be less relevant to payers for clinical or economic reasons.

Designs with uncertainty and subjectivity

When designing a non-inferiority study, the assumed treatment effect of the comparator is based on prior study outcomes and an assumption that the treatment effect will be the same in the non-inferiority study. But that quickly proves difficult as populations and treatments change over time. New combinations and adjuvant therapies muddy the waters. The trial design must also set the largest clinically acceptable degree of inferiority (i.e., the degree to which a product can fall short of expectations), which is a subjective determination. And let’s not forget the ubiquitous and potentially subjective and inconsistent study-design decisions related to endpoint(s), dose(s), inclusion and exclusion criteria, time point for assessing the endpoint, and study duration. Given the array of decisions to make, as well as the assumptions unique to non-inferiority trials, it is not surprising that payers are naturally skeptical of evidence based on non-inferiority studies.

Questionable motives

Payers may question the motivation of manufacturers that seek to demonstrate non-inferiority. Some payers may interpret evidence of non-inferiority as a lack of investment and commitment to power a study with sample sizes sufficient to demonstrate superiority. Alternatively, payers may interpret evidence of non-inferiority as attempts to avoid the risk that evidence of inferiority will surface, or —much worse — suppress evidence of inferiority.

When not bad is good

Payers typically want new products that are superior to alternatives, not non-inferior products. But there are scenarios where payers embrace non-inferior products. Payers love a new non-inferior product that costs much less than the alternatives. The potential for biosimilars — products deemed to be non-inferior to their respective reference products — to reduce spend is of great interest to payers. And payers may embrace a new non-inferior product that is self-administered versus one that is physician-administered, or one that has a safety profile that could yield medical-cost offsets. Non-inferior products that lack a compelling clinical or economic value proposition are often rejected, unless the new product brings welcomed competition to the market.

It depends

Have you noticed how good food tastes when you’re hungry? Even warm pancake batter is not bad if you’re very hungry and add enough syrup.

Manufacturers need to anticipate payers’ receptiveness to a new entrant’s non-inferiority designation, as payers can view the product as being fair, good, or even great. Doing so successfully begins with the ability to see the clinical and/or economic value of the designation through a payer’s eyes.

No Comments